Doing business in the U.S.: Which visa should you choose?

Is your business ready to expand into the U.S., or perhaps you have already made that move? While the market is lucrative and may seem similar to Canada, there are many complexities of doing business in the U.S. that must be considered. In Richter’s original four-part series, Overcoming the Border Barrier, our professionals, along with guest speakers that specialize in different areas of expansion, lead attendees through various aspects of working and doing business south of the border.

Session two: Working in the U.S.

In Session two, Richter Principal Jacinthe Marquis discussed U.S. immigration rules, the different visa classes and tax filing rules, and the nuances between doing business with – versus working in – the U.S.

It’s a common occurrence: you, as a business owner or executive, are travelling to the U.S. for a conference or meetings to discuss how to best expand your business in key states or cities. On your declaration card when crossing the border you simply check the “Business” box when asked why you are entering the U.S. and thanks to NAFTA, this will typically allow you to attend the conference or meeting as planned without further paperwork. However, if you are to spend longer periods of time in the States, or perhaps you need to send contractors or start employing people in regional areas, things can get more complicated.

Tax filings between the U.S. and Canada vary widely, and you can experience serious repercussions if you do not obey each law in each country. As you expand your operations, you also need to ensure you and your employees are compliant with the laws of working and living in the U.S., and filing taxes accordingly. Even if you have little intention of settling into the U.S. permanently, there are still many rules relating to tax filings with which you need to comply.

Under Federal rule, you would be considered a U.S. tax resident if you fit into one of three categories: 1) you become an American citizen (immigration), 2) you hold a permanent resident status or Green Card, or 3) you are considered to be a tax resident based on the outcome of a substantial presence test. It’s also worth noting that states within the United States have their own rules: it is possible to be a state resident and a federal non-resident at the same time. When operating out of certain states, become familiar with local state laws, in addition to federal laws.

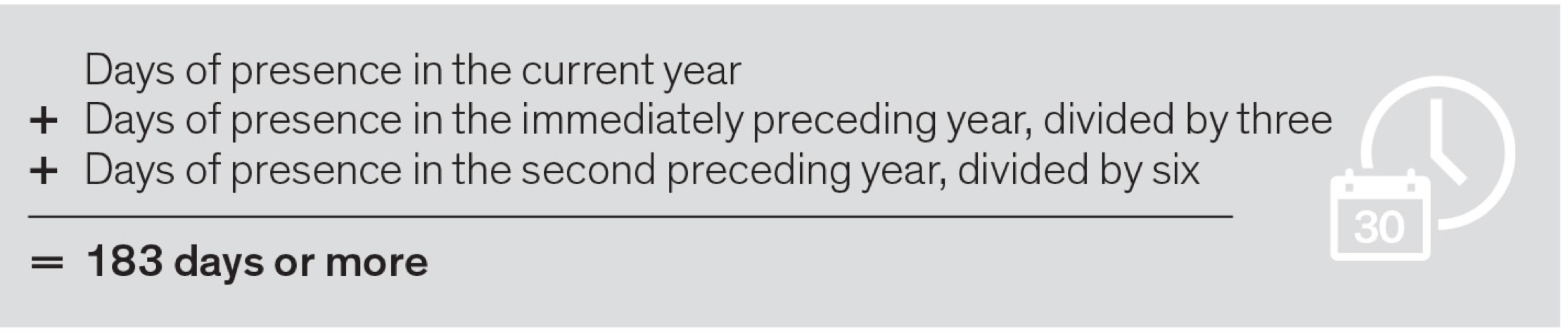

The category which involves the most preparation and in our experience, is the trickiest for most business people, is the substantial presence test. The U.S. has an equation in which the number of days you’ve spent on American soil are calculated; should you spend 183 days or more (partial days count as full days) of three calendar years in the U.S., you will most likely be considered a U.S. tax resident, and therefore have to pay U.S. federal taxes.

The equation to tally the number of days you’ve spent in the U.S. to be considered a U.S. tax resident is as follows:

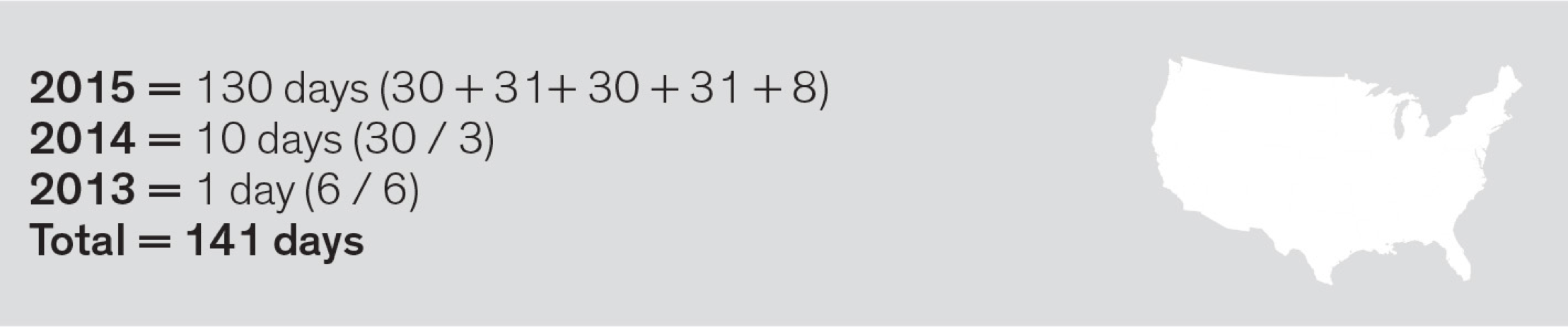

Example: Employee A commenced a quarterly assignment in the U.S. on September 1, 2015. He also spent eight vacation days in the U.S. in June 2015, 30 vacation days in 2014 and six vacation days in 2013.

Is he a U.S. tax resident in 2015?

As his 141 days spent in the U.S. is less than the requisite 183, no, he is not considered a U.S. tax resident.

While in this example the employee is not considered a resident, it is easy to see how quickly the days add up, especially as partial days are counted as full days toward the total. When you or your employees do travel frequently across the border, it is recommended that you monitor your “days of presence” in the U.S. closely. This could be as simple as keeping a log or journal to count both holiday and work days throughout the year. Should one of your employees be over the 183 day allowable limit, she or he may qualify for the Closer Connection Exception. This exception comes with its own conditions, and specific forms need to be filled out in order to comply.

There are a host of other rules regarding residency and employment income to which you must adhere when increasing your working presence (or that of your company’s or employees’ presence) in the U.S. While you can generally count on the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty to provide some relief, the Treaty does not assist in every way – and the big penalties lie where it doesn’t. The general rule to remember when it comes to the taxation of employment income: wages are subject to tax in the jurisdiction where services are rendered; but are also taxable in the jurisdiction of residency. There are different forms for reporting income in the U.S. depending on the type of income, but if an employee maintains Canadian residency, these funds are still reportable on a T4, as well. To avoid double taxation, proper assessment should be done to conclude which jurisdiction has the ultimate right to tax. If the income is self-employed, or under US$3,000, further rules will also apply. In general, it will still be subject to Canadian income tax withholding if the employee maintains Canadian residency.

Self-employment income is generally deemed taxable in the U.S. if it is “connected with a U.S. trade or business” but exempt under the Canada-U.S. Treaty if you do not have a “permanent establishment” in the States. Self-employed Canadian residents are most often also exempt from social security in the U.S., whereas employees of a company generally pay in the country in which services are rendered. However, because of the Canada-U.S. Social Security Agreement (SSA) there is an exemption from U.S. FICA for up to five years, which allows employees to pay into the Canadian Pension Plan on U.S. wages after applying for a certificate of coverage with the Canada Revenue Agency. Other considerations you should take under advisement include employment contracts and secondment documentation to manage your tax exposure, labour laws, employee responsibilities, and structural issues – would it make more sense to establish a U.S. subsidiary, or a branch office? Registered Pension Plans and RRSPs also have strict reporting requirements that vary country-to-country.

Stating that there is much to consider when expanding operations – especially if you are preparing your strategy for the long-term – is a big understatement, to say the least. Even though it can be overwhelming, it’s crucial to consider all options and establish the best plan for you and your business from the get-go whenever possible. While the rules are many, the consequences if you don’t comply can be severe.

In order to avoid difficult situations, and protect you, your staff, and your bottom line, it’s best to consult a professional business advisor for an objective opinion on how to make your move into the U.S. smooth and prosperous.