The Punchbowl’s Empty – What’s Next for Investors?

Authored by Greg Moore, CFA, FEA, Partner, Richter

Little did investors know that the 2022 New Year celebrations would mark the end of the “bull market for everything”. And at the same time potentially usher in a new era where investors need to rethink how and where they will be able to generate returns within their portfolios. As the Economist noted last December[1], given the events that have unfolded over the last nine months of 2022, “investors find themselves in a new world and they need a new set of rules”. So how did we get here and what does it mean for the future? And what new rules do investors need to be aware of?

Looking back, the multi-decade rally in bonds has been a big factor in support of portfolio returns. Since the peak of interest rates in the late 1970s and early 1980s, investors have had the benefit of a tailwind in fixed income as rates were on a steady decline until only recently. A generation of investors have known nothing but a secular bull market in fixed income securities. In addition to creating a good ballast for other risk assets (most notably equities), declining rates helped keep fixed income prices supported and juiced returns from capital gains. This meant that having a good allocation to bonds not only helped provide diversification to a balanced portfolio, they also, on balance, added to returns.

More recently, there has been an even more significant factor that has added to investor exuberance: liquidity. And lots of it.

After the Great Financial Crisis in 2008/2009, central banks around the world embarked on a massive liquidity plan to help stabilize financial markets. By acting as a buyer of government debt, “quantitative easing”, central banks have given governments around the world the green light to borrow with impunity – knowing that they will be there to buy their bonds and by extension, keep interest rates low. This worked well in an environment of low inflation. With a variety of factors conspiring to keep price pressures low, central banks had an easy job of achieving their primary policy goal of containing inflation. And because inflation was low, there was no urgency to tighten policy, which allowed them to just keep buying bonds, expanding their balance sheets, and supporting government spending.

Easy monetary policy paved the way for even more financial market liquidity during COVID; central banks were printing money to help governments finance massive direct transfers to households and businesses to offset the economic impact of shelter-in-place directives. This helped drive investor behaviour into overdrive. Liquidity was ample and interest rates were low. The punchbowl was brimming, and investors were happy to imbibe.

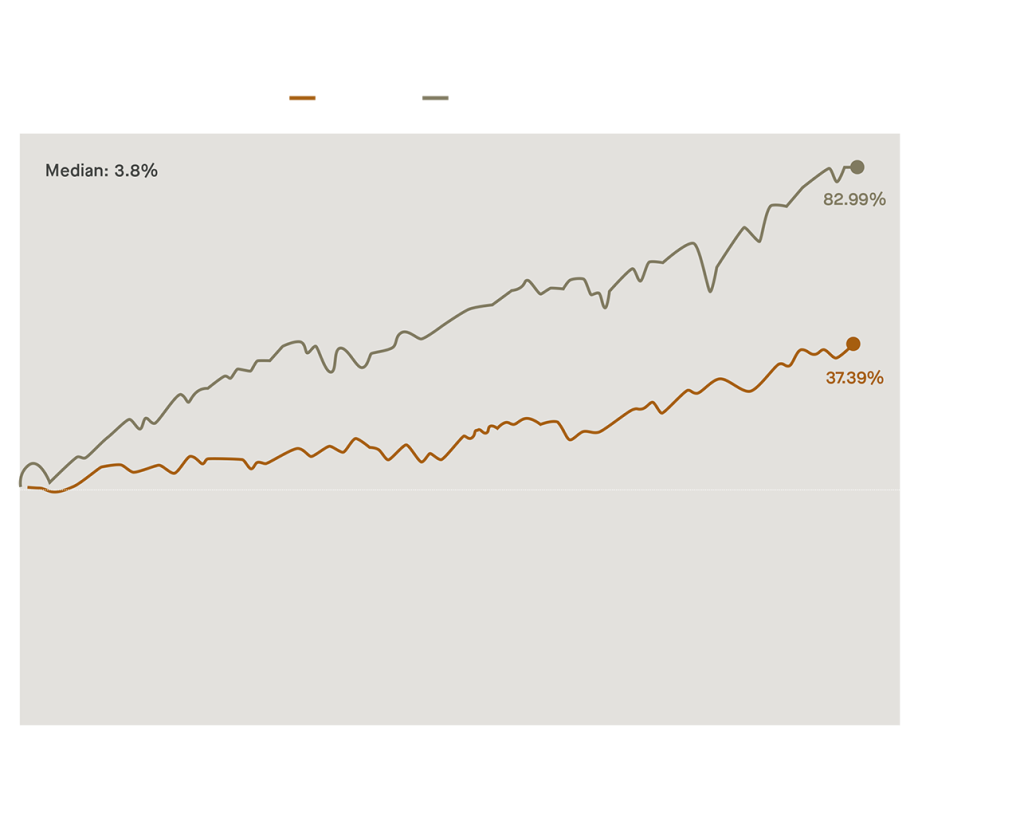

Recently, we had the opportunity to host a webinar with Joshua Lewin, a Senior Investment Associate from Bridgewater Associates. One of the most stunning data points that he referenced during our session highlighted the performance of a standard 60/40 portfolio of equities and bonds over each rolling ten-year period since 1970. The chart below shows that over the most recent 10-year period, investors experienced more than double the median historical return of a typical balanced portfolio of equities and bonds – far outpacing even the second most profitable period.

But all this changed in 2022. And the hangover caught just about every asset class across the globe, resulting in the worst collective performance for global stocks and bonds since the end of the Second World War.

So, what happened?

First, inflation started to rise. Households that were flush with cash went out and spent it during COVID. Absent being able to travel or dine out, they bought consumer goods at such a clip that manufacturers couldn’t keep up. Supply chains broke down under the pressure of shutdowns and consumer demand causing prices to climb. Initially, central banks and policy makers saw inflationary pressures as transitory, hoping that they would self correct as conditions “normalized”. But other factors conspired to keep inflation surging: the Russian invasion of Ukraine pushed energy prices sky-high; China closed due COVID restrictions, putting one of the world’s largest manufacturing bases on pause; and a shift away from globalization saw manufacturing costs rise as companies moved from “just in time” inventory management to “just in case” – moving manufacturing facilities to be geographically closer but at a higher cost base. Suddenly, inflation wasn’t so transitory anymore.

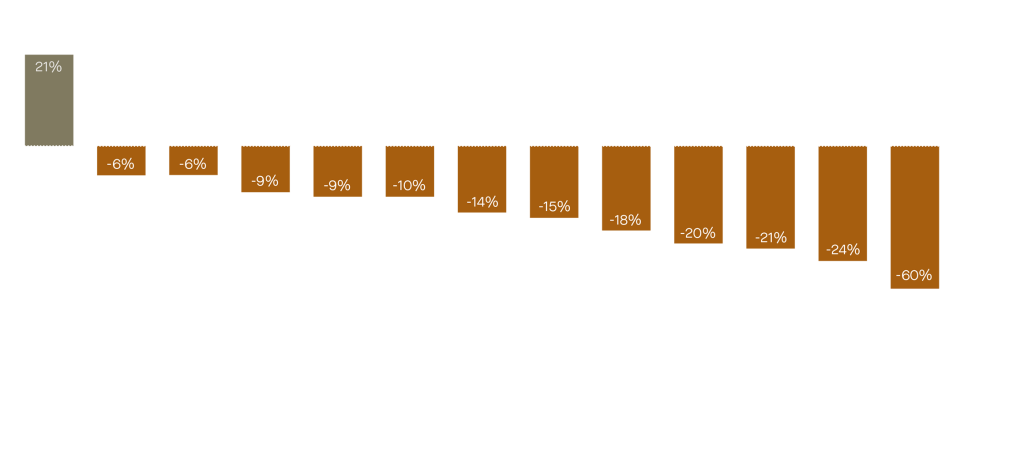

Central banks reacted quickly, going from buying financial assets at the fastest pace ever, to selling financial assets at the fastest pace ever. As a result, interest rates rose through 2022 at the fastest pace in modern financial history. As you would expect, risk assets have not reacted well; notwithstanding the recovery late in the year, returns across global asset classes to the end of September 2022 were dismal and indicative of financial markets that had overvalued risk assets across the board.

Fortunately, as the balance of 2022 played out, markets recovered materially as some evidence emerged that inflation was moderating, as are expectations now for higher interest rates. But forward expectations continue to price in a perfect scenario of an economic soft landing where corporate earnings will remain robust and the tailwinds that have supported savers and higher incomes will continue.

During our discussion with Joshua Lewin from Bridgewater, he reflected his firm’s position that many of the factors that supported corporate profits in the developed world (globalization, deregulation, and generally pro-corporate government policies) contributed significantly to asset price gains over the last decade. And in its opinion, many of these may be set to reverse. One of the greatest risks that Bridgewater has assessed is the growing wealth gap between the highest and lowest income earners across the developed world. For example, many of the pro-corporate policies favoured by developed nations have contributed to a situation whereby the share of the wealth held by the bottom 90% of the population is at the lowest level since the Great Depression. This has been a contributing factor behind growing political division and populism across the globe. If governments look to address growing income disparities to quell growing populist pressure, how would this impact corporate profits moving forward?

Certainly, governments may find themselves in a position of having to adopt policies that may favour a greater distribution of wealth. This means more profits in the hands of labour, and on balance, lower corporate profitability. This may manifest itself by way of higher corporate tax rates, less favourable government policies towards corporations, and stronger unions. It may also mean a shift away from the globalization that helped fuel the low-inflation environment of the last decade as governments look to enact protective polices designed to support domestic productivity and less reliance on foreign supply chains.

In short, many of the factors that have contributed to strong growth and low inflation may be conspiring to elevate inflation on a longer-term basis and at the same time challenge economic growth. This later scenario is generally not an environment that is supportive of equity prices or corporate bond spreads. Or more explicitly, a typical balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds.

So, what are the new “rules” that investors need to be cognizant of moving forward?

As Mr. Lewin pointed out during our discussion – “when in doubt, don’t predict. Diversify.” Over the last decade, the typical investor held a portfolio of assets that was largely correlated to positive growth and low inflation. Most notably growth-oriented equity securities and fixed-income. And the advent of “passive” or lower cost index solutions was also appealing, as it allowed for a cost-effective way to access the market return to an asset class that was in a secular uptrend.

Going forward, investors might be wise to diversify their portfolios in more ways than one, as the range of potential outcomes appears quite wide due to the reversal of the above long-term trends.

Firstly, diversification can be targeted across and within traditional and alternative asset classes and strategies. The TINA (“There Is No Alternative” – to stocks) trade appears to be stretched following a monumental run post the Global Financial Crisis. With low interest rates, investors exited the traditional balanced 60/40 approach in droves and instead heavily concentrated themselves in equities.

However, despite 2022 being the worst year for long-term U.S. Treasuries since 1754[1], the death of bonds might be greatly exaggerated (to paraphrase Mark Twain). As yields have risen and the correlation to equities is potentially normalizing, fixed income might well be on its way to resuming its long-term role as an effective diversifier to equities within the traditional portion of portfolios.

On the alternative side of things, assets such as real estate, commodities (including precious metals), royalties (tied to lithium, water, etc.), and others (intellectual property rights, litigation finance, etc.) offer risk/return outcomes tied to factors other than those driving stocks and bonds. Investors might also consider a variety of alternative strategies to help diversify portfolios by relying more on uncorrelated alpha or skill-based returns, versus layering on more beta or market risk.

Secondly, domestic investors should also consider diversifying outside of North America. Over recent years, many investors’ portfolios have become quite sensitive to a narrow collection of U.S. technology stocks (the so-called FAANG names). It is almost never the case that one jurisdiction leads equity market returns in back-to-back decades and this points to the need for global diversification, including Emerging Markets where valuations are much lower and whose local economies are growing and becoming less correlated to Developed Markets.

Lastly, portfolios can benefit from additional diversification and potentially profit from the illiquidity premium offered by private markets as a complement to public securities. This includes private equity, benefiting from the current trend of companies staying private longer, private credit (as banks have vastly reduced lending to small-medium enterprises post Global Financial Crisis regulations), private real estate, including specialty assets such as medical storage, and many other private markets. It is important to evaluate allocations to these private markets, as appropriate, considering the impact on overall liquidity within a portfolio.

RFO Capital would be more than pleased to discuss any of the above with investors that wish to continue this critical portfolio construction conversation in the current environment. We look forward to speaking with you.

Past performance is not indicative of future results.

The contents of this article are not meant for broad distribution and should not be considered a solicitation to transact in securities. The opinions of Bridgewater Associates, LP do not necessarily represent the opinions of RFO Capital Inc.

Richter Family Office is a registered trade name. The Richter Family Office group is comprised of Richter LLP and its subsidiary, RFO Capital Inc., a registered portfolio manager. Richter LLP is an independent firm that provides family office, accounting, tax and business consulting services, with wealth, investment advisory, portfolio management and consolidated wealth reporting services provided via RFO Capital Inc.

All registerable activities are performed uniquely by RFO Capital, an advising representative registered with the AMF, OSC, ASC and BCSC

[1] Searching for Returns: The New Rules for Investors, The Economist Magazine, December 9, 2022 [2] Iacurci, G. (2022, January 7). 2022 was the worst-ever year for U.S. bonds. How to position your portfolio for 2023, CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2023/01/07/2022-was-the-worst-ever-year-for-us-bonds-how-to-position-for-2023.html