Repricing risk in the times of COVID-19

Business Valuation and Dispute Advisory Group

Contact Person: Alana Geller, CPA, CA, CBV, CFF

This article was published in the CBV Institute’s Journal of Business Valuation (November 26, 2020 edition)

View an update of Richter’s COVID-19 Timeline.

Author’s Foreword:

This article was written over the course of the summer and completed in August 2020, before the second wave of pandemic impacted much of the developed world and before the 2020 US election. We have not amended the article for these and other factors relevant at the date of printing. However, at the time of proofing this for publication in mid-October, the same valuation perspectives remain relevant, namely:

- Amplification and acceleration of pre-existing trends;

- Acceleration of growth in digital, internet and related businesses;

- Continued low interest rates and widening spreads for risky assets;

- The market’s willingness to look ahead to a new normal at modest discount rates;

- Extraordinary dependence on subsidies and government stimulus;

- Gap between winners and losers continues to widen;

- Irrecoverable loss of value in various service, commercial and retail sectors;

- The implications of the disconnect between wall street and main street are unknown at this time;

- The timing and effective dissemination of a vaccine is closer now than in March 2020, and remarkable strides have been made, but timing remains unclear;

- The “new normal” remains undefined.

Considering these and other factors, there remains an important role for the valuation profession in these unprecedented times.

Warren Buffett said, “Risk comes from not knowing what you are doing”. In volatile times like these, there are many unknowns and variables that give rise to significant valuation risks and opportunities.

Since March 2020, certain industries have been hit hard, some have demonstrated resilience and others have enjoyed accelerated growth. Industry and company-specific factors must be applied to more generic inputs to produce a sound valuation analysis. The discounted cash flow (DCF) method should be the primary approach during this period.

When markets are in turmoil, what is the meaning of “fair” in the definition of fair market value’ (FMV)? If markets were temporarily rendered illiquid and inefficient, should the prohibition against hindsight evidence be relaxed to help the valuator arrive at a better valuation conclusion?

We hope this article will help you explore these and related ideas – and as always help distinguish value from price.

The COVID-19 landscape

What was known or knowable and what did the market say?

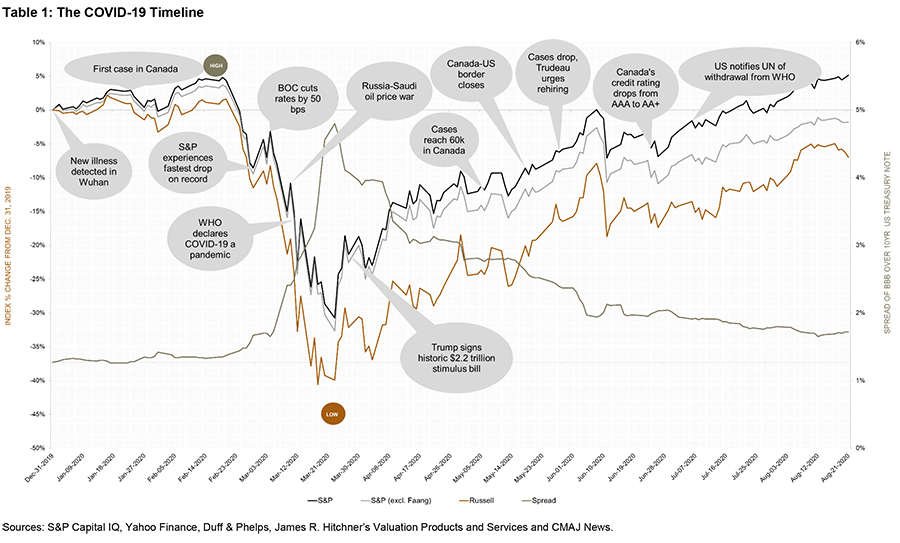

At the time of writing, some indices had rebounded to pre-COVID-19 levels, but a second wave and subsequent volatility remain a possibility. History has shown that private markets are not as volatile as public ones, and we believe this remains true during the pandemic. Public market data during COVID-19, as it applies to private company valuation, must therefore be used with greater caution and professional skepticism.

The rebound of the stock and credit markets following the low in March 2020 was meaningfully bolstered by remarkable government stimulus, particularly in Canada and the US. The level of funding provided and the impact on the economic environment could not have been predicted at the outset of the pandemic. Further, at the time of writing, it is difficult to predict the level of government stimulus that will persist and its impact on corporations, industries and the macro economic climate.

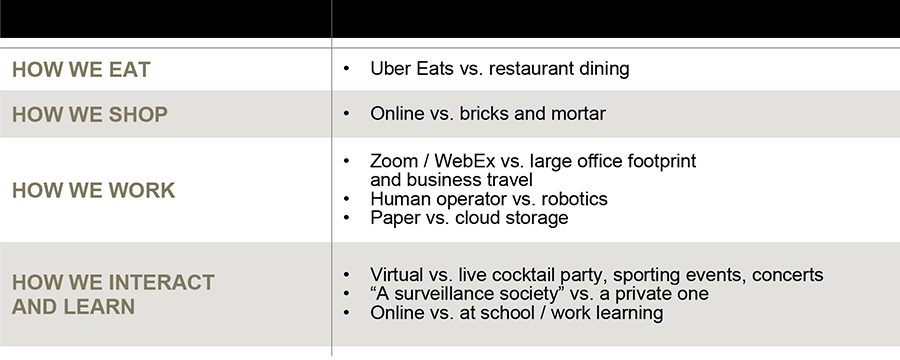

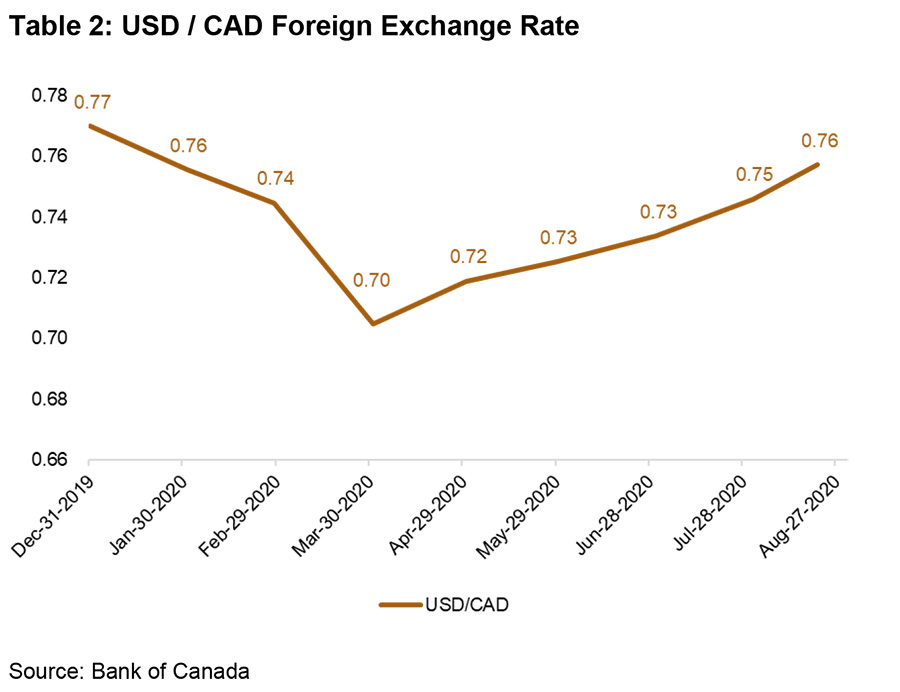

There were many pre-existing social, business, industry and technological trends occurring simultaneously with the pandemic; many of these were accelerated or more pronounced as a result of the pandemic. Trends such as the continued shift and greater emphasis towards online shopping, remote working and learning, the concern for sustainable environmental practices and migration away from fossil fuels. Simultaneously, there were important world events which had a dramatic impact across virtually all industries and economies, including: the Saudi Arabia/Russian oil crisis, trade issues with China, low interest rates, increasing nationalism, and ballooning sovereign debt. During the height of the pandemic, North American and European equity and credit markets were in flux and private and public deal volume was down. There have been some signs of stabilization in recent months, and deal activity has also been picking up as of late. The Canadian dollar has also rebounded to pre-pandemic levels (Table 2).

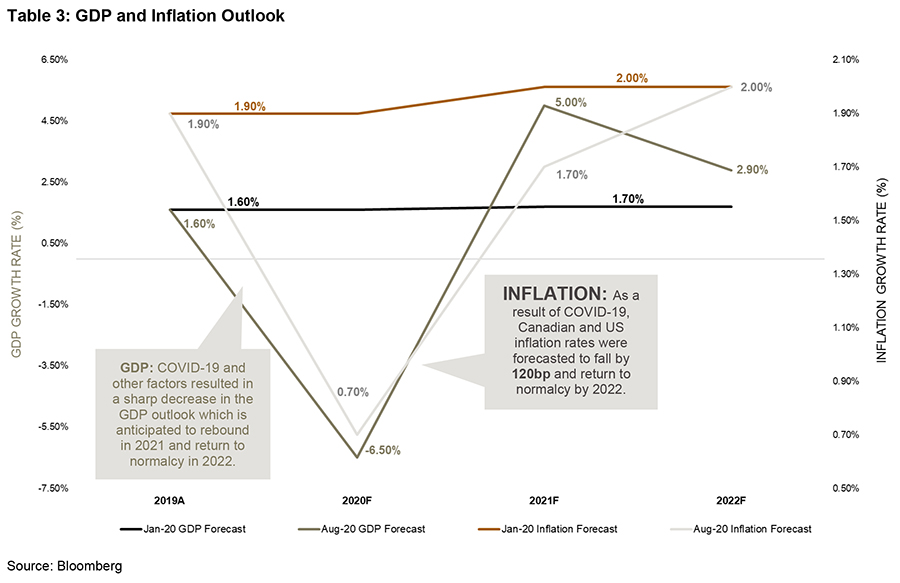

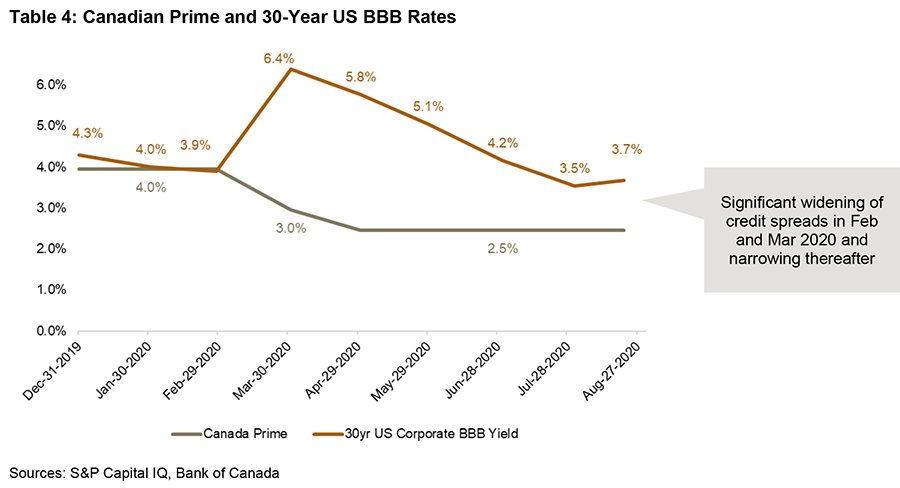

Are these trends and concerns temporary or permanent? How should a business valuator account for them? COVID-19 and other factors resulted in a sharp decrease in the GDP outlook, which is anticipated to rebound in 2021 and return to normalcy in 2022 (Table 3). Key lending rates all fell in March 2020 with no rebound to August 2020 (Table 4). At the same time, yields on corporate bonds have fallen since their high in March 2020. These factors, along with fears of a second wave of COVID-19 are real, and potential consequences of this wave and other trends and events need to be considered when determining FMV.

Acceleration of pre-existing trends – temporary or permanent?

It’s been discussed at length, but in short: depressed sales, supply chain upset, and massive layoffs for some, while others are experiencing a surge in demand and are facing new challenges as they try to scale up. We are seeing dramatically different sectoral performance and trends, but there are significant differences in how companies within the same industry have dealt with the challenges presented. Whatever the result, there is often a significant impact to FMV which cannot be overlooked, and company-specific analysis remains important.

Is it a trend? Or here to stay? COVID-19 has impacted almost all aspects of our lives:

Where are we at? Where are we going?

Overall, based on market data: the number of transactions in Canada is down approximately 40% based on a year-over-year comparison from March 1 to July 31, 2020.[1]

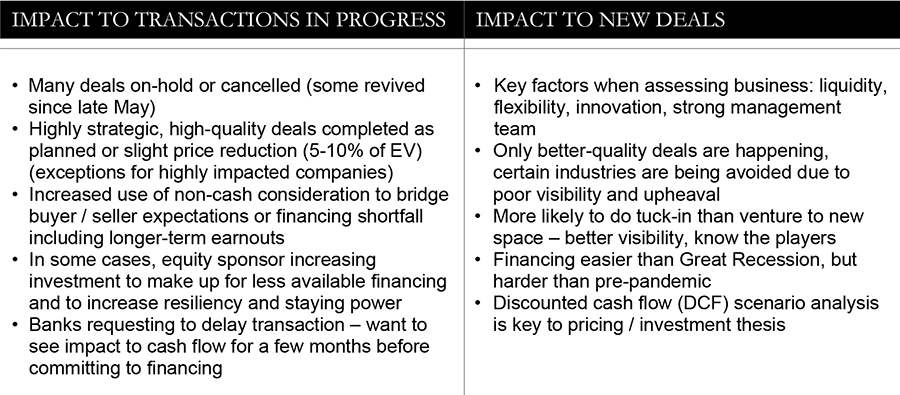

The following insights are based on an informal survey of institutions, PE / VC Funds and family offices in May/June 2020 and our own observations:

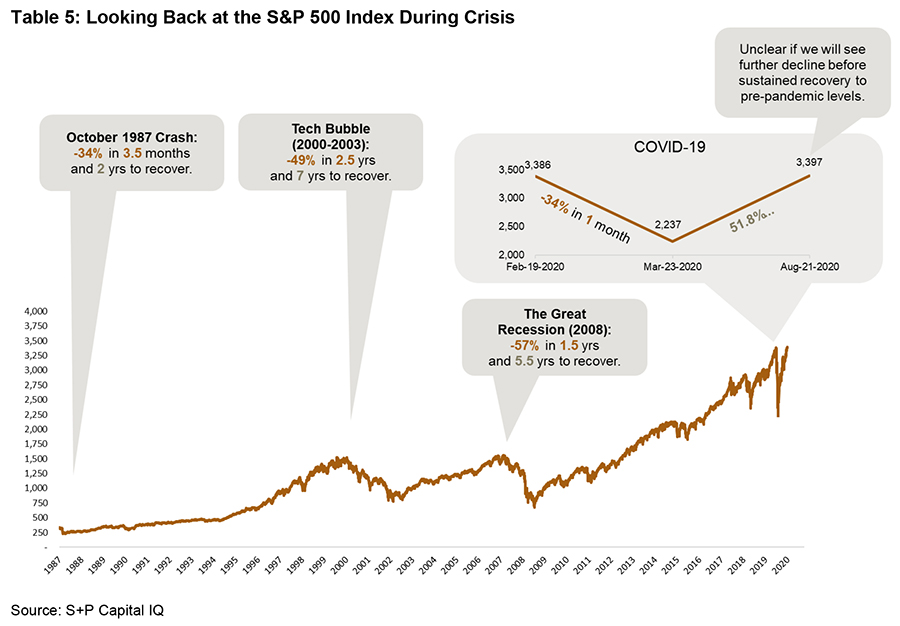

Table 5 illustrates how the S&P 500 performed during past crises – it has taken two to seven years to recover in the past, far longer than the time to crash, and there may be many waves up and down before the recovery is complete.

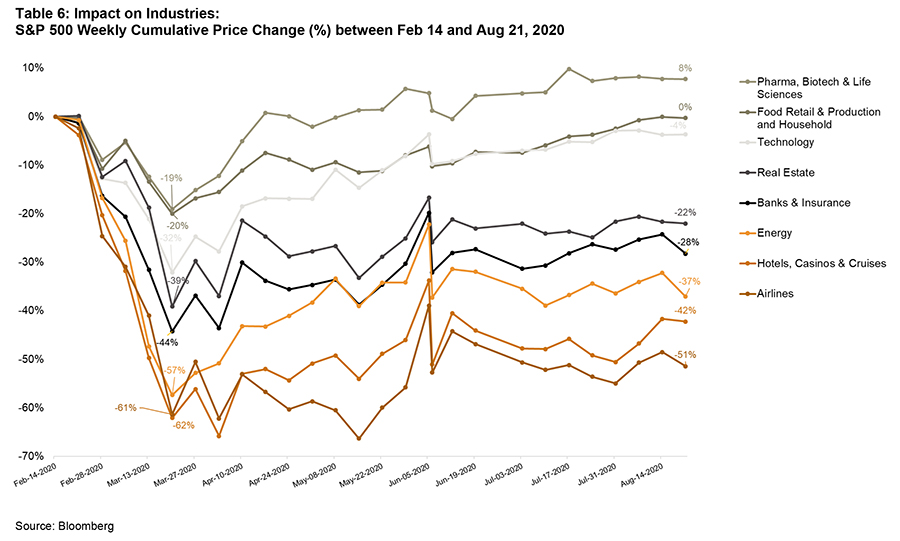

Industry: the good, the bad, and the ugly

Not surprisingly, between mid-February and August 2020, pharma and biotech more than recovered, while energy and travel are still very depressed. It is important to remember though, that stats for any industry are just averages. Some companies will prevail through innovation, flexibility / ability to pivot, access to liquidity and other factors, while others will perform worse than their peers. Perhaps most importantly, the market is not a good proxy for intrinsic value. It does help with some directional impact, but company-specific analysis and an assessment of company-specific factors are of utmost importance.

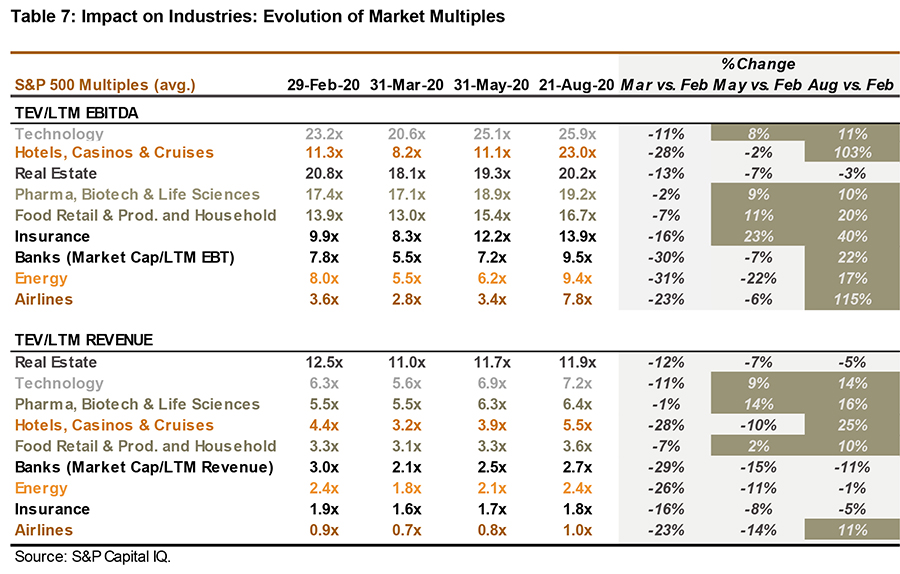

Table 7 summarizes the evolution of multiples by industry. By May 31, 2020, multiples for sectors impacted less by the pandemic had recovered and by August 31, 2020, multiples had recovered for almost all industries. With that said, earnings were significantly down for many industries, leading to overall lower valuations (with some exceptions). Trading multiples should be viewed with skepticism.

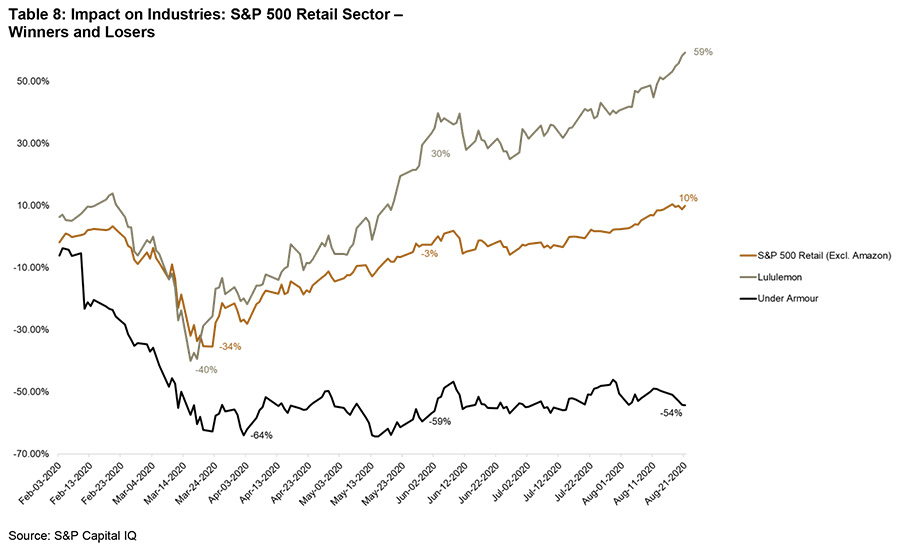

For example: Table 8 shows the S&P Retail Index against Lululemon – which many of us have been sporting as our new remote working attire – versus Under Amour, a brand that was struggling pre-pandemic and has seen an accelerated negative trend:

This further exemplifies that the struggles companies experienced pre-pandemic were further exacerbated during the pandemic.

Value definition and the use of hindsight

When markets are illiquid or inefficient, it is important to understand how ‘fair’ modifies the definition of FMV and whether there is legitimate use of hindsight beyond the testing of the reasonability of assumptions as permitted by the hindsight principle.

When the target business and the valuation date circumstances are more uncertain than normal, assumptions in notional valuations will be equally uncertain. The more risk in the business generating the cash flow, the more risk that the valuation result will be flawed.

What is ‘fair’?

How does the word ‘fair’ modify ‘market’ and ‘value’ in times of turbulence and market volatility? Are quoted market prices indicative of a fair value and / or fair market? Case law certainly opens the door that quoted market prices and the volatility of the market are not necessarily equal to FMV or fair value. Several definitions of FMV suggest market data from consistent markets should be given much more weight than when drawn from markets in flux. One definition of FMV is “the value obtained in a normal market, that is,

a market which is not disturbed by unusual economic factors and where vendors, ready but not too anxious to sell, meet with purchasers ready and able to purchase.”[2] To further quote case law: “market price must have some consistency and not be the effect of a transient boom or a sudden panic on the market”.[3]

Will the pandemic’s impact on stock prices be considered a “transient boom or sudden panic” on the market? Or a long-awaited correction? As earlier discussed, it is important to distinguish “transient boom or sudden panic” effects from more permanent effects for which the pandemic was only a catalyst. Price volatility alone does not preclude a market from being deemed consistent; a distinction can and should be drawn between normal volatility – say in the technology, pharma or mining industries as the result of a resource discovery or significant innovation – in contrast to a “transient boom” based on fear mongering and emotions as might have been evident during the pandemic.[4] A global, panic driven sell-off may result in selling prices that are not equal to FMV.

What does the case law say about hindsight?

“Hindsight or retrospective evidence is the consideration of facts and events occurring after a specific date in question, such as a valuation date or breach date”.[5]

Jurisprudence validates the hindsight principle: “I expressly rejected the validity of hindsight as probative of fair market value at a given date and took nothing that occurred after Valuation Day into account.”[6] In notional business valuations, courts have generally held that hindsight evidence cannot be used except to test the validity / reasonableness of assumptions at the valuation date and/or obtain a better understanding of facts or conditions which are known or knowable at the valuation date – i.e. the “hindsight principle”.

However, in the rare circumstances where there is no other data available, exceptions have been made: “Since the market for artwork experienced such significant changes within a short period of time before and after the financial crisis, the Court found that such factors must be taken into account in determining an appropriate value for the three paintings.”[7]

When there is a lack of good quality data, is hindsight a means of mitigating an inefficient market? If so, its appropriate use might be limited. Consider the following:

- How long is the period, post-valuation date, during which it is appropriate to consider hindsight information? We believe a few months may be permissible. For example, for March to May 2020 valuation / damages dates, the subsequent market rebound might be a permitted use of hindsight.

- When valuing a business at a Spring valuation date, could the valuator rely on hindsight data from the Fall to confirm “second wave” effects? It seems to us that in the Spring of 2020 the second wave was a real risk that had to be assessed as one could best do at that time. However, the occurrence (or not) of an actual second wave, is too long past the Spring valuation date to be considered in the valuation.

Other cases and commentary that address the use of hindsight are set out in the Appendix.

For the purposes of quantification of damages, facts and information related to the period after the alleged wrongdoing is generally admissible.[8] Damages are compensatory by nature and seek to place the injured party in the same position that it would have enjoyed but for the wrongdoing. Simply, the quantum reflects “what would have happened” less “what actually happened”. What “actually happened” will reflect events that occurred after the damages date. Therefore, it is appropriate to consider hindsight data when determining “what would have happened”. Essentially, “hypothesis should not replace history”.[9]

Impact to methodology and cost of capital during covid-19

Where to start?

A thoughtful discussion is a good place to begin, which will help the valuator assess the impact of the pandemic on the subject business:

- The business plan – how was it updated, who was involved, was it stress tested?

- Customers and suppliers – evaluate health, pipeline, and various risks and opportunities.

- Products and services (availability, volumes, price) – consider supply chain upset, impact to

pricing, demand. - Operations – changes to key overhead costs, impact of government assistance programs.

- Liquidity – cash runway, covenants, collateral assessment, working capital requirements.

- Profitability – when is the company expected to return to the pre-COVID-19 level of profitability? What is the expected impact on long-term profitability?

The answers to the above questions will help determine the appropriate valuation approach and point the analysis in the right direction.

Selecting an approach

We believe a cash flow-based model accompanied by thoughtful sensitivity or scenario analysis is essential when preparing a valuation in a time of financial crisis. Consider the following:

- Income Approach:

- DCF is a preferred approach but its major pitfall is a lack of good quality projections.

- Capitalized cash flow or income methods are suspect as the “normal / sustainable” cash flow

or income to be capitalized may be difficult to determine. Relevance of trailing twelve months must be carefully considered and synchronized with the right multiple or discount rate. It is almost impossible to capture the potential volatility of the recovery to “normal” using capitalization rates or multiples. - Some analysts are assuming a return to ‘normal profits’ within six to 24 months and discounting back to the valuation date, specifically adjusting for interim profit / loss. While this approach seems reasonable, it introduces a further element of uncertainty.

- Market Approach is still appropriate in the current environment, however, anomalous inputs, the thin market, and comparability must be very carefully considered.

- Asset Approach often relies on historical data which may be outdated. Further, use caution with reliance on reports qualified due to the pandemic and related matters.

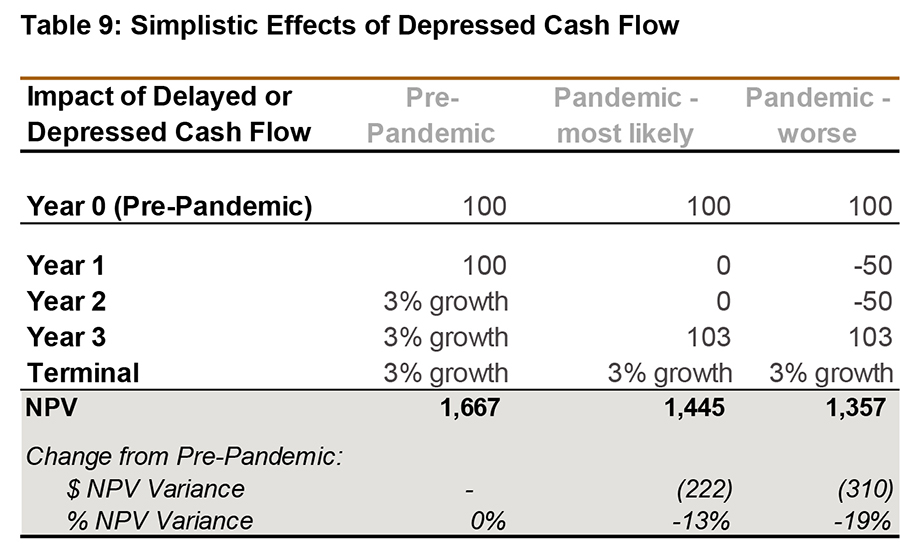

Effects of depressed cash flow

Does one or two poor years matter? In a time where buyers are seeking discounts and quality sellers are holding firm on price, who has it right? Table 9 illustrates how one or two years of poor performance can have a significant downward impact on value. The impact on equity value would be much more significant

if the business were levered.

These are simple scenarios for illustrative purposes. Scenarios should thoughtfully contemplate various economic, industry and company-specific outcomes including access to liquidity to fund potential negative cash flows.

Access to liquidity is key and could have a significant impact on value. Access to financing was initially expected to be very constrained but governments have provided enormous liquidity to the debt markets and corporate lending to larger entities has been much easier than anticipated. Lending to smaller businesses has been and was predicted to be more sporadic and constrained.

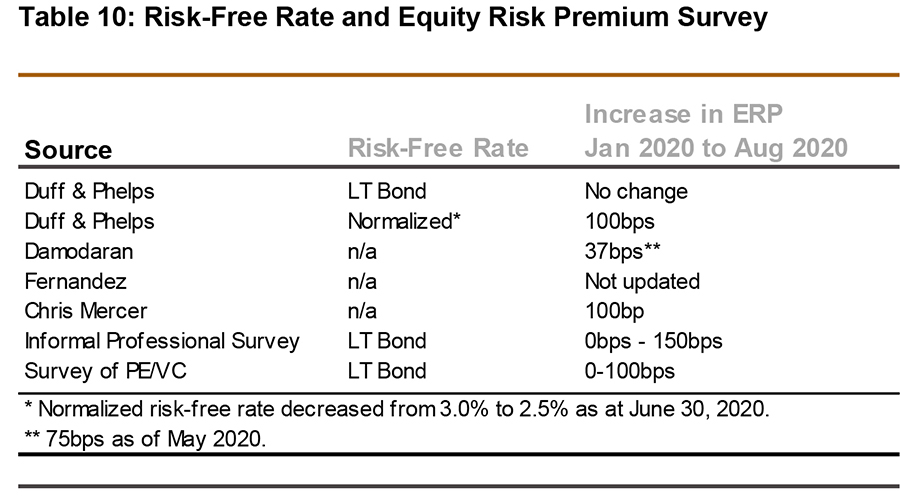

Impact on rates of return to be used in business valuations

Both sector and company-specific factors must be considered. Many thought leaders continue to use spot interest rates to determine rates of return but have offset this reduction with an increase to the equity risk premium (Table 10). Despite decreased spot interest rates, spreads have increased, resulting in a higher cost of debt. As a result, for some companies but not all, discount rates have trended higher.

Consider using a lower level of “optimal” debt to allow for a greater operational financing cushion. It is best practice to adjust both the cash flow and the rates of return and ensure that the two are properly calibrated to capture risk appropriately.

Marketability discounts are likely impacted by covid-19, at least in the short-term

Each investment needs to be assessed using specific facts; and when assessing marketability discounts for minority interests, context is very important. Since February 2020, we believe, in general, that marketability discounts have increased as a result of the factors below – albeit partially offset by a lower risk-free rate of interest:

- Decreased access to financing for the underlying business and the purchase of the minority position itself.

- Decreased M+A activity and a reduced pool of willing buyers.

- Increased supply side of secondary investments as institutions seek to divest to rebalance and/or meet regulatory requirements.

- Reduced expected profitability, cash flow and longer realization timelines.

- Increased perceived risk and demand of higher returns.

Notwithstanding the above, over time, a prolonged period of low interest rates, a lack of investment opportunities, large amounts of investable cash available and comfort with risk may moderate the marketability discount range.

In summary

Whether for a notional or transaction-oriented valuation, companies and valuators should take the time to prepare and assess the company’s projections to understand how the company is most likely to weather the pandemic. While market data may be directionally helpful, deep forward-looking company-specific analysis is key to arriving at a reasonable and thoughtful conclusion.

This article was written by Richter LLP’s Business Valuation and Dispute Advisory Group.

Contact Person: Alana Geller, CPA, CA, CBV, CFF

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and not necessarily those of Richter. Richter does not guarantee the accuracy or reliability of the information provided herein and the views and opinions expressed herein may change. The information herein was compiled as of August 21, 2020 or as noted; some information may have changed since that date.

Appendix: Fair Market Value Vs. Market Value

“Fair Market Value” (“FMV”) is defined as “the highest price, expressed in terms of cash equivalents, at which property would change hands between a hypothetical willing and able buyer and a hypothetical willing and able seller, acting at arm’s length in an open and unrestricted market when neither is under compulsion to buy or sell and when both have reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts”.

FMV is not specifically defined in the Income Tax Act.

“Market Value” refers to the current or most recently-quoted price for a market-traded security.

It can also refer to the most probable price an asset, like a house, would fetch on the open market.

Bellow, we summarize definitions of FMV that can be found in jurisprudence.

Appendix: Additional FMV References in Jurisprudence

- “Where there is a ready market for shares such as the stock exchanges provides for its listed shares, the market price, as revealed in regular market quotations, is probably the best but not necessarily the only indication of value.”(Minister of Finance v. Mann Estate, 1972).

- “The expression “fair market value” is well known in law and, indeed, there is little dispute before me as to the definition of the term…I do not intend to quote at length from these authorities, but it is clear, from an examination of them, that the expression “fair market value” means the exchange value, the value an asset will bring in the market and, where no market exists, that value must be determined by other indicia of value.” (Minister of Finance v. Mann Estate, 1972 , Grimes v. The Queen, 2016 TCC 280, and others).

- “In determining the fair market value where there is no competitive market at the date as of which the value is to be ascertained, other indicia may be resorted to…There may be reasonable prospects of the return of a market, in which case it might not be unreasonable for the assessor to evaluate the present worth of such prospects and the probability of an investor being found who would invest his money on the strength of such prospects; and there may be other relevant circumstances which it might be proper to take into account as evidence of its actual capital value.” (Smith v. Minister of National Revenue, [1950] S.C.R. 602, Montreal Island Power Co. v. Town of Laval des Rapides, and others).

- “Canadian Courts have generally considered the word “value” when it is contained in legislation, regulations, contracts and other legal documents to be synonymous with market value or fair market value.” (Pocklington v. Alberta (Provincial Treasurer), 1998 ABQB 279).

Appendix: Other Cases and Commentary that Support Use of Hindsight

- “For purposes of determining fair market value, we believe it appropriate to consider sales of properties occurring subsequent to the valuation date if the properties involved are indeed comparable to the subject properties’….Of course, appropriate adjustments must be made to take account of differences between the valuation date and the dates of the later-occurring events….When viewed in this light—as evidence of value rather than as something that affects value—later-occurring events are no more to be ignored than earlier-occurring events”. (Estate of Jung v. Commissioner, 101 T.C. 412, 431-432 (1993)).

- “Courts have not been reluctant to admit evidence of actual sales prices received for property after the date of death, so long as the sale occurred within a reasonable time after death and no intervening events drastically changed the value of the property” (First National Bank v. United States, 763 F2d 891 (7th Cir. 1985)).

- “When a subsequent event such as the third sale before us is used to set the fair market value of property as of an earlier date, adjustments should be made to the sale price to account for the passage of time as well as to reflect any change in the setting from the date of valuation to the date of the sale…These adjustments are necessary to reflect happenings between the two dates which would affect the later sale price vis-a-vis a hypothetical sale on the earlier date of valuation. These happenings include: (1) Inflation, (2) changes in the relevant industry and the expectations for that industry, (3) changes in business component results, (4) changes in technology, macroeconomics, or tax law, and (5) the occurrence or nonoccurrence of any event which a hypothetical reasonable buyer or a hypothetical reasonable seller would conclude would affect the selling price of the property subject to valuation (e.g., the death of a key employee)”. (Estate of Helen M. Noble, v. Commissioner (Noble), T.C. Memo 2005-2 (January 6, 2005)).

- “Referencing appropriate transactions is a critical facet of the Market Approach to valuations. Particularly when valuing the stock of closely held companies, guideline transactions can shed useful light on the value of the subject company. There is established legal precedent in the tax court for valuation practitioners to take into account certain events taking place following the valuation date; however, in such cases the amount of time that has passed matters. The decision in the referenced Noble v. Commissioner case stated that “in determining the value of unlisted stocks, actual sales made in reasonable amount at arm’s length, in the normal course of business, within a reasonable time before or after the basic date, are the best criterion of market value””. (Flieger, S. (2016). Case In Point: Valuation Case: “Time Changes Everything”).

- “While there were several court conclusions, with regard to the valuation issues the court found little merit in Sumner’s expert’s “engrafting method” arguing in particular that citing a reference transaction from 1984 was not particularly relevant to a valuation date of July 1972. The court found that not only had too much time passed in general, but too much had changed for NAI and the industry as a whole in the interim 12 years for reliance on a redemption price from 1984. The court agreed with the tax court’s expert opinion that the June 1972 settlement agreement was the more relevant transaction”. (Flieger, S. (2016). Case In Point: Valuation Case: “Time Changes Everything“).

- The Court extensively reviewed the issue of hindsight and American jurisprudence before ruling. Relying on a judgment by the Court of Appeal for the Eighth Circuit which held that, in determining the value of unlisted stocks, actual sales made within a reasonable time before or after the valuation date were the best criteria of market value. The Tax Court did not consider the two sales made prior to the valuation date to be comparable transactions due to the size of the shareholdings. The sale of the actual 11.6% interest subsequent to the valuation date was the most relevant comparable transaction since it was for the exact shares under consideration. The Court found no material changes in the circumstances of Glenwood between the valuation date and the subsequent sale, concluding that an “event occurring after the valuation date, even if unforeseeable as of the valuation date, also may be probative of the earlier valuation to the extent that it is relevant to establishing the amount that a hypothetical buyer would have paid a hypothetical willing seller for the subject property as of the evaluation date.”” (Canadian Institute of Chartered Business Valuators, Valuation Casebook (2015). Noble — Estate of Helen M. Noble v. Tax Commissioner of Internal Revenue 2005 T.C. Memo — United States Tax Court (p.331).

- “Opening the door to the routine analysis of subsequent transactions as providing evidence of valuation at earlier dates would seem to fly in the face of the basic intent of the fair market value standard of value… The questions and issues raised by Estate of Noble are important for appraisers and for taxpayers. Regarding subsequent transactions, it would seem that appraisers and the Tax Court should focus on events known or reasonably foreseeable as of the valuation date as the basic standard for fair market value determinations. Any other approach would seem to raise more questions than can be answered, and would seem to place at least one party in a valuation dispute at a distinct disadvantage.” (Mercer Capital, When Is Fair Market Value Determined? Estate of Helen M. Noble v. Commissioner.).

Appendix: Scope of Review

We reviewed and relied upon, as appropriate, information contained in the following documents and interviews:

COVID-19 Landscape

COVID-19 Timeline: Impact to S&P 500 and Debt Spreads, What Was Known or Knowable at the Valuation Date?:

- Duff & Phelps’s webinar “Coronavirus: Cost of Capital Considerations in the Current Environment” presented by Carla S. Nunes, Managing Director, and James P. Harrington, Director, on April 16, 2020;

- Valuation Products and Services LLC’s “COVID-19: A timeline of Significant Events, Including the Pandemic’s Effect on the U.S. Stock Market” prepared by James R. Hitchner, CEO and Karen A. Warner, Managing Editor; and

- CMAJ News’s “COVID-19: Recent Updates on the Coronavirus Pandemic”, Lauren Vogel and Laura Eggertson, May 29, 2020.

Value Definitions and the Use of Hindsight

Fair Market Value vs. Market Value:

- Withycombe Estate / Attorney-General of Alberta v. Royal Trust Co., 1945 CanLII 22 (SCC), [1945] SCR 267;

- Untermeyer Estate v. Attorney General for British Columbia, 1928 CanLII 43 (SCC), [1929] SCR 84; and

- Henderson v. Minister of National Revenue, 1973 CarswellNat 189, [1973] C.T.C. 636, 73 D.T.C. 5471 (Federal Court—Trial Division).

Use of Hindsight – General Application in Valuation and Damages:

- The Canadian Institute of Chartered Business Valuators (CBV Institute) – Valuation Casebook, 2015;

- Wise, Blackman LLP’s Value Wise, Volume 1, No. 1, “Is Hindsight Admissible in Business Valuation?”, April 2006; and

- CBV Institute, Business Valuation Digest “The Use of Hindsight in Damages Quantification – Beware a Valuation Approach”, by Peter Steger (Steger, 1999).

Use of Hindsight in FMV During COVID-19, What Can be Learned From Case Law?:

- National System of Baking of Alberta Limited v. Her Majesty The Queen (1978 DTC 6018 — Federal Court, Trial Division, 1980 DTC 6178 — Federal Court of Appeal);

- Holt v Inland Revenue Commissioners 1 W.L.R. 1488 (25 November 1953);

- Dailley Recreational Services Ltd. v. Minister of National Revenue (1984 D.T.C. 1680 — Tax Court of Canada);

- Canadian Institute of Chartered Business Valuators, Valuation Casebook (2015): Airst v. Airst (1998 O.J. No. 2629 — Ontario Court of Justice) (p.12);

- Estate of Jung v. Commissioner, 101 T.C. 412, 431-432 (1993); and

- Flieger, S. (2016). “Case In Point: Hindsight in Valuation? Yes. Maybe”.

Impact to Methodology and Cost of Capital During COVID-19

Marketability Discounts Are Likely Impacted by COVID-19, at Least in the Short-Term:

- Chris Mercer Useful Business Valuation Information & Insights “What is the Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis on Marketability Discounts (DLOMs)?”, by Chris Mercer, May 18, 2020.

Cost of Equity – Risk Free Rate is Down, Other Factors are Case Specific:

- “Implied ERP by Month for Previous Months” as of June 2020 by Aswath Damodaran at www.pages.stern.nyu.edu;

- IESE Business School, “Survey: Market Risk Premium and Risk-Free Rate used for 81 Countries in 2020” by Pablo Fernandez, Professor of Finance, Eduardo de Appelaniz, Research Assistant and Javier F. Acin, Independent Researcher, March 25, 2020;

- Chris Mercer Useful Business Valuation Information & Insights “What is the Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis on Marketability Discounts (DLOMs)?”, by Chris Mercer, May 18, 2020; and

- KPMG’s “Survey Results: Valuation Inputs and Assumptions Amid COVID-19 Uncertainty (Q1 2020)”, May 12, 2020.

Appendices

Appendix: Additional FMV References in Jurisprudence:

- Minister of Finance v. Mann Estate, 1972;

- Grimes v. The Queen, 2016 TCC 280;

- Smith v. Minister of National Revenue, [1950] S.C.R. 602 and Montreal Island Power Co. v. Town of Laval des Rapides; and

- Pocklington v. Alberta (Provincial Treasurer), 1998 ABQB 279.

Appendix: Other Cases and Commentary that Support Use of Hindsight:

- Estate of Jung v. Commissioner, 101 T.C. 412, 431-432 (1993);

- First National Bank v. United States, 763 F2d 891 (7th Cir. 1985);

- Estate of Helen M. Noble, v. Commissioner (Noble), T.C. Memo 2005-2 (January 6, 2005);

- Flieger, S. (2016). “Case In Point: Valuation Case: Time Changes Everything“;

- Canadian Institute of Chartered Business Valuators, Valuation Casebook (2015): Estate of Helen M. Noble v. Tax Commissioner of Internal Revenue 2005 T.C. Memo — United States Tax Court (p.331); and

- Mercer Capital, When Is Fair Market Value Determined? Estate of Helen M. Noble v. Commissioner.

We also reviewed other publicly available information such as S&P Capital IQ, Yahoo Finance, Bloomberg, Bank of Canada, Federal Reserve, The Conference Board of Canada and CEIC Data.

Lastly, we conducted interviews with several Canadian PE / VC Firms, private family offices, banks, pension funds and professional firms.

[1] S&P Capital IQ, based on announced and closed deals with value greater than $5M, excluding real estate and resources.

[2] Withycombe Estate / Attorney-General of Alberta v. Royal Trust Co., 1945

[3] Estate of Isaac Untermeyer v. Attorney-General for the Province of B.C.,1928.

[4] Henderson Estate v. Minister of National Revenue, 1975.

[5] CBV Institute

[6] The Queen v. National System of Baking Alberta Ltd., 1978. Other similar cases include Holt v. IRC, 1953, Dailley Recreational Services Ltd. V. MNR, 1984, Airst v. Airst, 1998.

[7] Estate of Bernice Newberger, et al., v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue.

[8] “Is Hindsight Admissible in Business Valuation?” (Wise, Blackman, LLP, 2006)

[9] “The Use of Hindsight in Damages Quantification – Beware a Valuation Approach” (Steger, 1999)